Overview of Longplayer

What is Longplayer?

Longplayer is a one thousand year long musical composition. It began playing at midnight on the 31st of December 1999, and will continue to play without repetition until the last moment of 2999, at which point it will complete its cycle and begin again. Conceived and composed by Jem Finer, it was originally produced as an Artangel commission, and is now in the care of the Longplayer Trust.

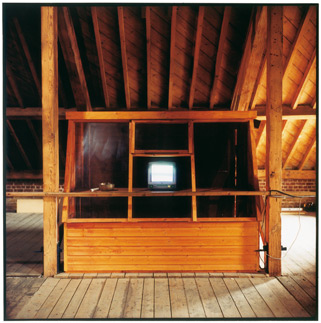

Longplayer can be heard in the lighthouse at Trinity Buoy Wharf, London, where it has been playing since it began. It can also be heard at several other listening posts around the world, and globally via a live stream on the Internet.

Longplayer is composed for singing bowls – an ancient type of standing bell – which can be played by both humans and machines, and whose resonances can be very accurately reproduced in recorded form. It is designed to be adaptable to unforeseeable changes in its technological and social environments, and to endure in the long-term as a self-sustaining institution.

The Long Term

Longplayer grew out of a conceptual concern with problems of representing and understanding the fluidity and expansiveness of time. While it found form as a musical composition, it can also be understood as a living, 1000-year-long process – an artificial life form programmed to seek its own survival strategies. More than a piece of music, Longplayer is a social organism, depending on people – and the communication between people – for its continuation, and existing as a community of listeners across centuries.

An important stage in the development of the project was the establishment of the Longplayer Trust, a lineage of present and future custodians invested with the responsibility to research and implement strategies for Longplayer’s survival, to ask questions as to how it might keep playing, and to seek solutions for an unknown future.

Composition in Time

Longplayer is composed in such a way that the character of its music changes from day to day and – though it is beyond the reach of any one person’s experience – from century to century. It works in a way somewhat akin to a system of planets, which are aligned only once every thousand years, and whose orbits meanwhile move in and out of phase with each other in constantly shifting configurations. In a similar way, Longplayer is predetermined from beginning to end – its movements are calculable, but are occurring on a scale so vast as to be all but unknowable.

Longplayer’s composition uses a minimum amount of information and material to create the maximum amount of variety, in terms of both sound and form. While it is a system-based composition, it is made out of very expansive and resonant musical material, which in itself is not ‘systematic’ sounding. This material (the ‘source music’) is played on Tibetan singing bowls, which possess a simple but harmonically rich sound, and a quality which is at once both physical and ethereal. A simple form of synthesis arises from the interactions of these instruments’ waveforms, with the consequence that while Longplayer’s score is deterministic, its music at any given time is unpredictable.

Technology

At present, Longplayer is being performed mostly by computers. However, it was created with a full awareness of the inevitable obsolescence of this technology, and is not in itself bound to the computer or any other technological form.

Although the computer is a cheap and accurate device on which Longplayer can play, it is important – in order to legislate for its survival – that a medium outside the digital realm be found. To this end, one objective from the earliest stages of its development has been to research alternative methods of performance, including mechanical, non-electrical and human-operated versions.

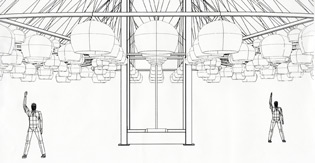

Among these is a graphic score for six players and 234 singing bowls. The first performance based on this score took place over 1,000 minutes on 12 – 13 September, 2009, at the Roundhouse, London. Longplayer Live is performed on a vast, specially-constructed instrument by an orchestra of players working in shifts. A series of further performances are in planning for various venues around the world – see the Live page for more information.

Who Created Longplayer?

Longplayer was developed and composed by Jem Finer between October 1995 and December 1999, with the support and collaboration of Artangel. It was managed by Candida Blaker, with a think tank comprising artist Brian Eno, British Council Director of Music John Keiffer, landscape architect Georgina Livingston, Artangel co-director Michael Morris, digital sound artist Joel Ryan, architect and writer Paul Shepheard and writer and composer David Toop. A full account of Longplayer’s development can be found in the 2003 book Longplayer, published by Artangel, London.

Jem Finer is a UK-based artist, musician and composer. Since studying computer science in the 1970s, he has worked in a variety of fields, including photography, film, music and installation. Longplayer represents a convergence of many of his concerns, particularly those relating to systems, long-durational processes and extremes of scale in both time and space. Among his other works is Score For a Hole In the Ground, a permanent musical installation in a forest in Kent. Self-sustaining and relying only on gravity and the elements to be audible, the project continues Finer’s interest in long-term sustainability and the reconfiguring of older technologies.

Based in London and working both in the UK and internationally, Artangel has been commissioning and producing ambitious projects by contemporary artists for the last two decades. Often surprising in both conception and scale, each project begins with an invitation to an artist to develop a new work, inspired and given shape by a particular place. Artangel works closely with the artist to realise the full potential of the work in whatever form, medium and context seems best. Since the early 1990s, Artangel has produced over fifty major new commissions including Rachel Whiteread’s House (1992), Michael Landy’s Breakdown (2001), Francis Alys’ Seven Walks (2005) and Heiner Goebbel’s Stifters Dinge (2008). Artangel is supported by the Arts Council of England and The Company of Angels. Visit www.artangel.org.uk for more information.

Longplayer started playing at three separate listening posts in London and Sydney at 00:00 hours (IDLE) on the 1st of January 2000 (i.e. midnight on the International Date Line – midday on the 31st of December 1999 in London).